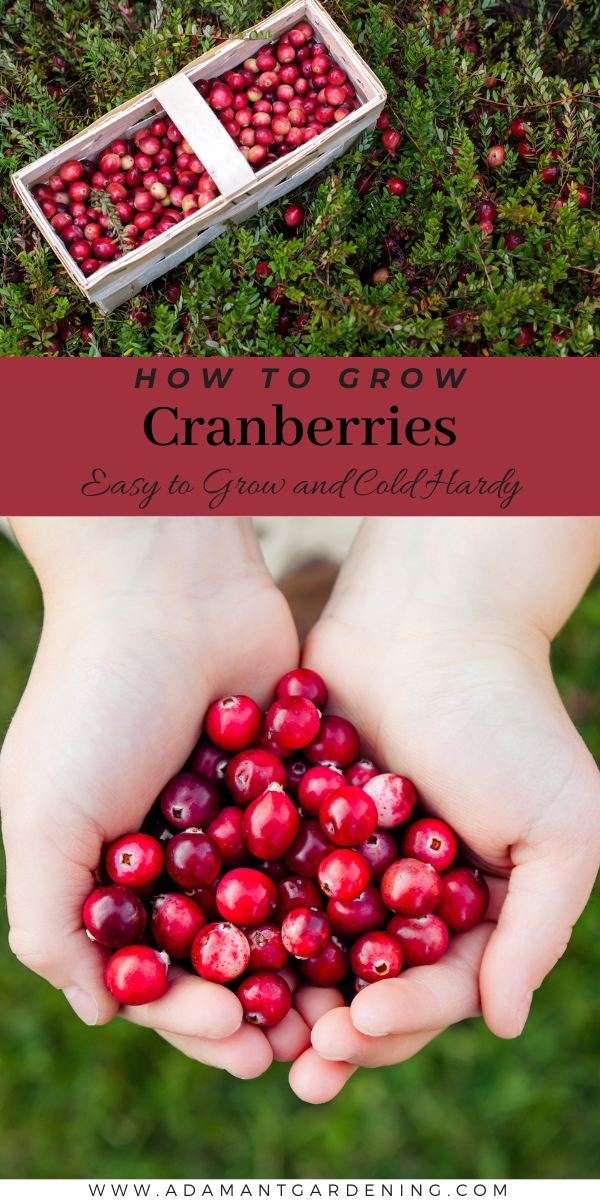

Growing cranberries is surprisingly easy!

Cranberry Plants

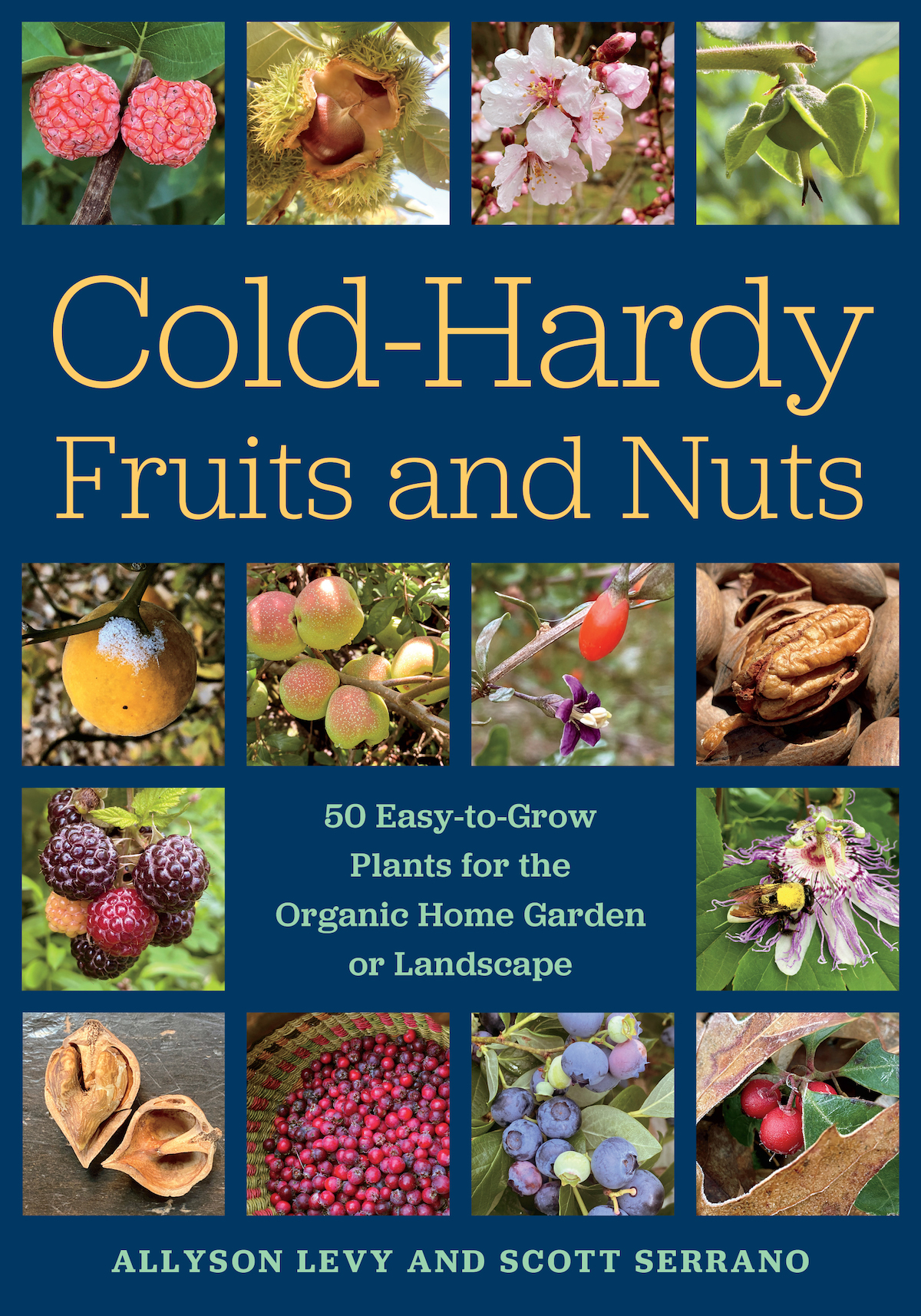

The following excerpt is from Allyson Levy and Scott Serrano’s book Cold-Hardy Fruits and Nuts (Chelsea Green Publishing, Mar 2022) and is reprinted with permission from the publisher. It has been edited slightly for format and length to fit the web.

Growing Cranberries

The use of wild cranberries for food and medicine goes back hundreds of years into the origins of the First Nations tribal cultures. Countless Indigenous tribes gathered harvests of cranberries, which were called sassamenesh by the Algonquin peoples and ibimi by the. Wampanoag tribes.1 English colonists to the United States quickly learned from Native tribes that cranberry was a useful wild fruit that could be paired with fresh game in their meals, and centuries later this is still the traditional accompaniment to the Thanksgiving turkey dinner.

The popularity of the fruit spread among the settlers of New England, and the first commercial cranberry bog was started by Captain Henry Hall in Barnstable, Massachusetts, in 1812.

The first book solely devoted to cranberries was published in 1856, titled A Complete Manual for the Cultivation of the Cranberry, by B. Easterwood, to cater to American farmers’ interest in a growing industry. By the time of the 1899 US census, no fewer than twenty-seven different states were growing cranberries as an agricultural crop.

Today cranberries are not only a major food crop but have been rediscovered as a superfood by a modern world that has finally caught up to the Native tribal peoples’ understanding that the berries can be used for medicinal remedies because they contain many healthful compounds that help reduce urinary tract infections.

Given the right conditions of consistently moist and acidic soil, this is an easy ground cover to grow, one that is fairly pest-resistant and will flourish in the correct soil conditions, that are consistently moist and acidic.

Taste Profile and Uses

Cranberries are 1⁄4 to 1⁄2 inch (0.6–1.3 cm) in size and start out white, then ripen to a deep burgundy color in the fall. Cooler autumnal temperatures produce the best deep-red-colored berries, which can occasionally be damaged by the onset of abnormally warm autumn temperatures.5 All of the berries generally ripen at one time and have a distinctive astringent flavor that is too strong for fresh eating but is one of the great cooking fruits. When cooked with other fruits, they impart a wonderful tangy flavor to sauces and are great for relishes and desserts. The juice itself is sour, but sweetening it allows cranberries to be enjoyed throughout the year, although any sugar added to the juice negates its health benefits. In recent years cranberries that are dried and sweetened have become a popular snack and an addition to granola.

Cranberry Harvest

Plant Description

An evergreen ground cover with creeping vines that forms a dense spreading mat by producing woody stems that sprout delicate, 1⁄4-inch (6 mm) long, glossy alternate leaves ranging from narrow ellipses to oval shapes. The woody stems are known as runners or stolons, and can spread many feet from the original plant. In spring the buds in the axils of the leaves produce several vertical shoots called uprights. These upright stems pro- duce the flower buds and slowly grow out and bend down into the tangled mass of the vine over time.

Flowers

Dainty flowers are formed on the upright stems, each producing between five to ten blooms. The buds first appear as little hooks along a pinkish-red petiole; then the petals and the sepals peel back to reveal the stamens, which gives the flowers the appearance of the head and beak of a crane. (The English colonial settlers called them craneberries because the flower was thought to resemble the head of a sandhill crane.6) Individually the tiny white to whitish pink blossoms are not overwhelming, but to see a large patch of these unusual flowers is quite beautiful.

Pollination Requirements

Cranberry is said to be self-fertile, but because the plants sold through nurseries are generally small, it is best to plant several individual vines to produce larger harvests.

Site and Soil Conditions

Cranberries are grown commercially in bogs that replicate the plants’ moisture requirements and also serve as an easy way to facilitate large-scale fruit production. For the home gardener it is best to try to mimic the fruit’s wild grow- ing conditions on a small scale, which is easier than it sounds (see the “Constructing a Small Cranberry Bog” section below). Cranberries can take some shade, but the best fruit production is accomplished in full sun with the vine’s root systems growing in acidic soil with a good amount of organic matter and sand. They also can be planted in average garden soil conditions with some acidic amendments, but the plants will need to be consistently watered through the drier parts of the summer.

The best growing conditions for cranberry are when the root systems are constantly moist but the sections of the vine growing out of the soil are not standing in water during the warm months of the year, when the vines are actively growing, because this can cause diseases and can damage plants.7 Cranberries require some air respiration around their root systems to be healthy during the period in which they are growing. This is why cranberries are only flooded (or covered with snow) during the winter for protection, since the root systems require much less respiration and stop most growth.8 For the winter the plants can be left alone or given some mulch to protect them in the colder parts of the United States.

Constructing a Small Cranberry Bog

This sounds like a massive excavation project with a bulldozer but it is actually simple to accomplish on a small scale when you understand that a “bog” is anything that holds moisture throughout a growing season and allows the roots of moisture-loving plants to thrive in the right soil conditions. Cranberries have root systems that spread out and are shallow, so any low plastic container that contains moist soil but permits extra rainfall to drain away from the plants will allow the vines to thrive. Below is a simple way to create a small bog, but this example could be expanded into a bigger area using a large impermeable thick plastic sheet inside of a shallow hole.

Creating a Bowl Bog: Use any watertight plastic container that is big enough to allow several plants’ roots systems to spread out—at least 8 inches (20.3 cm) deep. Dig a hole in the ground large enough to fit the entire container so that it sits flat on the bottom of the hole with the top of the container resting about 1⁄2 inch (1.3 cm) below the top of the planting area. Fill the container to the top with a three-part mixture of sand, garden soil, and an acidic amendment such as pine duff or peat moss; plant the vines into this soil and slowly add water until it completely saturates the soil up to the top of the container. Then use the original soil from the hole to pack around the perimeter of the container until it covers over and hides the edges of the bowl.

Hardiness

The hardiness range is dependent on the cultivar, but wild cranberry plants are rated hardy to zone 2 or −50°F (−46°C). Fertilization and Growth: Cranberry is slow growing, so it is best to use several plants in one area. They grow by horizontal runners that spread out, and after many years they become crowded and tangled up with one another, which ultimately reduces the amount of sunlight that can reach the lower parts of the vines. An annual pruning back of some of the vigorous runners in early spring will add to the productivity of the plants and increase air circulation around their roots. Applying a mulch every two years in spring composed of an acidic medium such as pine needles or pine duff, mixed with sand, will help protect new shallow cranberry roots and introduce some acidic nutrients to the soil. The first year that cranberries are planted, they should be watered about once a week if the top area around the plants is dry to a depth of 2 inches (5.1 cm). Then after a year the plants should thrive if they receive consistent rain throughout the season, but may need watering during prolonged periods with no rain

Cultivars

A century ago there were many cultivars of this fruit developed for different regions of the United States, with various ripening times and disease resistance.9 While there are still many cultivars of cranberry used on commercial farms, these plants are not available at retail plant nurseries; only a few varieties are available to the gardener.

‘Pilgrim’: A hybrid cultivar introduced in 1961 that produces abundant crops of large, purplish red berries that ripen late in the season.

‘Stevens’: A vigorous and productive cultivar with deep red fruit that ripens midseason. It was introduced in 1950 and is tolerant of poor soil.

Related Species

The small cranberry (V. oxycoccos) is a European relative that is closely related.

Propagation

This plant is most easily propagated by digging up small runners of the vine with some roots attached to the bottom of the stems, then repotting them in acidic, sandy soil. The plants can also be propagated through cuttings potted up with a mixture of sand, compost, and peat moss for a few years until their root systems are larger.

Pests and Problems

If your plants are properly sited in the correct soil conditions, they can often be fairly pest-free. Cranberries can get a few insect pests and root diseases, but we have never had any problems. The worst damage to our plants was by voles that spent one winter destroying most of our vines; after this it took a few years for our plants to grow back. Unopened flower buds and young flowers can be damaged by late-spring frosts, which is one of the reasons commercial cranberry farmers flood their crops.

About the Authors

Allyson Levy and Scott Serrano are both exhibiting visual artists and co-directors of Hortus Arboretum and Botanical Gardens in New York’s Hudson Valley. Their garden began as a source of inspiration and raw materials for their art. Over time their interest in growing a wider selection of plants expanded until the garden encompassed eleven acres and became their primary passion. Along the way they began planting a vast diversity of plants, both edible and ornamental. This grew into an extensive collection of cold-hardy cactus, magnolia trees, viburnums, and grafted fruit trees, with a focus on rare, underutilized plants. The arboretum is now a nonprofit organization and level II arboretum.

Leave a Reply